The guided-missile cruiser USS 'Princeton' steams through the night.

U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Logan C. KellumsWe love to count ships. We need to love talking strategy just as much. A new book by Jerry Hendrix—a naval historian and analyst and former U.S. Navy aviator—is a good place to start.

Naval observers fretted when, during the administration of U.S. president George W. Bush, the front-line U.S. fleet shrank from more than 300 ships to around 280.

For years, the administration of Pres. Barack Obama aimed to grow the fleet to 308 ships—but only managed to add a few vessels before, in its final months, it upped the goal to 355 ships.

Pres. Donald Trump’s administration maintained the 355-ship ambition but did almost nothing actually to make it a reality. Trump’s naval planning collapsed into confusion and bureaucratic infighting, slowing the Navy’s growth to just 295 ships in 2020.

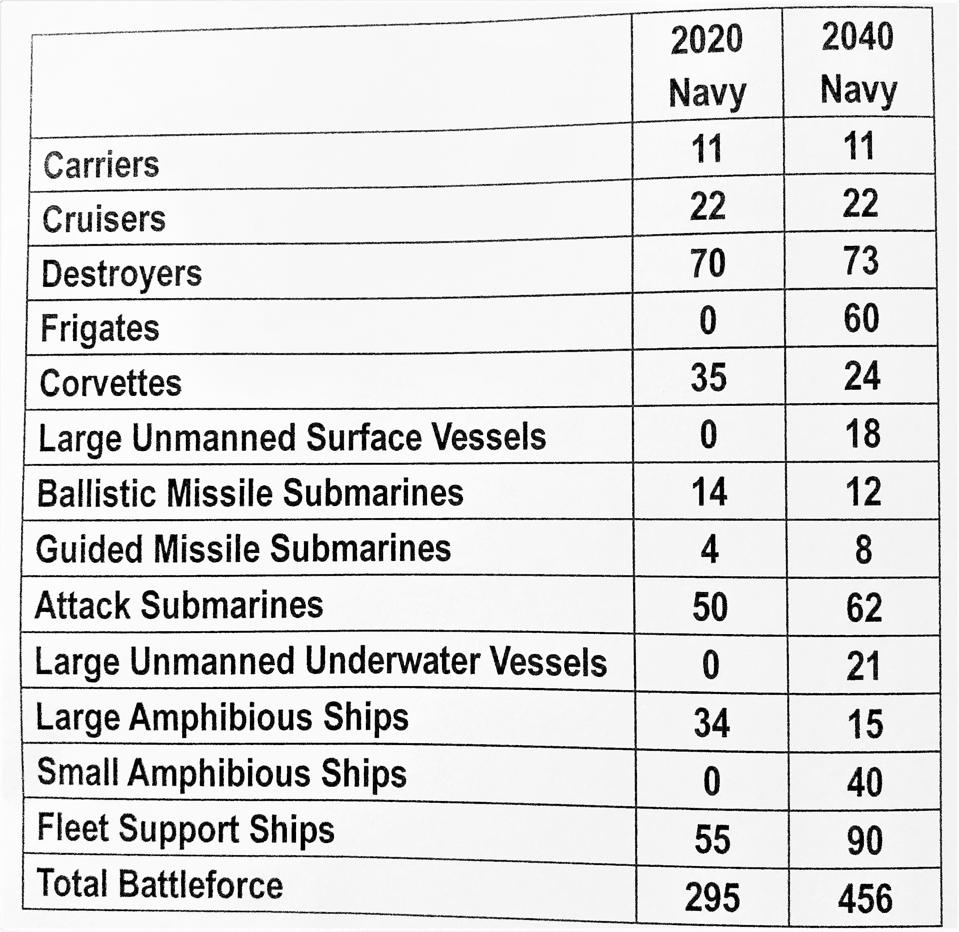

Then in its final weeks, the Trump White House added scores of unmanned vessels to its long-term shipbuilding plan—additions that would grow the Navy to nearly 400 major warships in the 2030s.

Rarely in this political tug-of-war over fleet counts have many officials specified what the ships are for. Why does the U.S. Navy need 308 ships, 355 ships or 400? In short—what’s the strategy?

MORE FOR YOU

In his short, breezy new book To Provide and Maintain a Navy, Hendrix starts with strategy before pitching his own ship-count.

It’s not that there’s no strategy underpinning a 308- or 355-ship fleet plan, of course. It’s just that policymakers rarely explain that strategy—or explain it well.

“I think there is an assumption of a strategy from so many of these [counts], an intuition of the nation’s strategic place in the world that does not require explanation,” Hendrix said, “but I have noticed over the past decade of writing the so many policymakers and just plain people do not understand those concepts or accept those assumptions, which is why I chose to try to tell the whole strategic story.”

Hendrix neatly summarizes America’s naval strategy. The sea is the global commons, the major medium of world trade, Hendrix explains. Free trade depends on free navigation—and that depends on an open, rule-based international order.

At the same time, there’s a moral imperative—to preserve and advance political systems that protect freedom, according to Hendrix. As a world power far removed from its major rivals and global conflict zones, the sea is the means by which the United States asserts its moral authority.

That’s the strategy. But strategy exists in a context of resources and threats. The resources America was willing to devote to sea power declined during the height of the country’s ongoing counterinsurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan starting in 2001.

The cash crunch helps to explain the consistent failure of successive presidential administrations significantly to grow the fleet. That under-resourcing created a power vacuum as fewer American ships were available to patrol the global commons and deter aggression.

America’s main rivals China and Russia have rushed to exploit that power vacuum. Both countries are growing and modernizing their fleets—and actually using them to pursue their own disruptive and authoritarian strategies.

“The old saying goes, ‘the enemy gets a vote,’” Hendrix explained, “and they voted and headed out while we were preoccupied in Afghanistan and Iraq.”

“Now the nation faces two rising great powers that each possess nuclear weapons, a fact that all but negates the option to attack, occupy and garrison them with land forces in a future war,” Hendrix writes.

“The United States must change its orientation back toward the sea, making a conscious decision once again to become a sea power, if for no other reason than that China and Russia, the recognized rising great powers, are already making the disruption of the oceanic global commons the center of their own strategic plans.”

On this basis, Hendrix proposes an American fleet that can both maintain a forward, deterrent presence and surge powerful forces for major warfare far from home—all in the face of increasingly powerful Russian and Chinese fleets.

Jerry Hendrix

Hendrix’s fleet isn’t radically different than the one the Trump administration proposed in its final weeks. The major differences are that Hendrix wants a much bigger logistics flotilla, many more frigates and eight new guided-missile submarines.

The additions make sense in light of the strategy Hendrix describes. Frigates can both patrol during peacetime and join battle groups during war. Logistics ships help supply this far-flung combat fleet. New guided-missile submarines are a potent surge force for the most intensive naval battles.

It’s an expensive fleet, of course. To buy, man and maintain all these new ships, annual Navy budgets would need to grow from around $200 billion to around $240 billion, Hendrix estimates. “While this number may seem large, it is right in line with inflation-adjusted Cold War naval expenditures,” he writes.

What will it take for the United States to build this fleet? “Leadership with a strategy to win, the vision and passion to sell it on Capitol Hill and in the White House and then the money and energy to drive change into the processes inside the Pentagon and the Department of the Navy,” according to Hendrix.

“We will need a strong civilian Navy leadership team who will know what handles to pull to change the direction of the ship before its too late.”

The Link LonkJanuary 04, 2021 at 08:00PM

https://ift.tt/3o883L3

To Restore American Sea Power, Stop Counting Ships And Start Talking Strategy - Forbes

https://ift.tt/2CoSmg4

Sea

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/CZF6NULMVVMEXHOP7JK5BSPQUM.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment