by Timothy Oleson

Friday, August 8, 2014

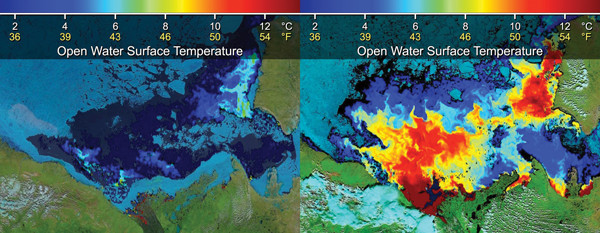

Sea-ice extent and open-water surface temperatures in the Beaufort Sea changed dramatically between June 14 (left) and July 5, 2012 (right), during which the barrier of "landfast" sea ice blocking the mouth of the Mackenzie River (left image, bottom) gave way. Credit: NASA.

In September 2012, the area of the Arctic Ocean covered by sea ice was the smallest on record since satellite monitoring began in 1979. Several factors are thought to have contributed to that summer’s diminished ice, including a large cyclone in August that brought warmer ocean waters into the area and broke up the ice and a longer-term trend of thinning and weakening sea ice. Now, researchers have found that at least one large burst of warm freshwater into the Arctic earlier in the summer probably played a role as well.

The scientists looked at data collected by NASA’s Terra satellite as it passed over the mouth of Canada’s Mackenzie River, which empties into the Beaufort Sea in the Arctic, on June 14, 2012, and then again on July 5. Analyzing the size and surface temperatures of the open-water expanse in the Beaufort Sea, they saw dramatic changes over the three-week period. The area of open water — where almost all traces of sea ice had melted — had grown by roughly 50 percent to 316,000 square kilometers, and surface temperatures in this expanse had increased by an average of 6.5 degrees Celsius, with warmer temperatures occurring close to the river’s mouth.

The Mackenzie — among the largest of more than 70 rivers flowing into the Arctic — drains fresh surface waters from 1.8 million square kilometers of land, making it the second-largest river watershed in North America after the Mississippi-Missouri system. Summertime insolation over the continent “provides a tremendous amount of heat that warms up these waters, which carry north and go into the Arctic Ocean,” says Son Nghiem, a senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and lead author of a new study reporting the satellite observations in Geophysical Research Letters.

The fresh river water not only arrives heated, but is more buoyant than the frigid and salty Arctic seawater, meaning much of the warm water remains at the ocean surface and in contact with floating sea ice. Adding up the annual contribution of all the rivers flowing into the Arctic, the heating potential is tremendous, Nghiem says. The influx of warm river water, which does not occur in Antarctica, may explain, in part, why Arctic sea ice “has been decreasing dramatically, whereas the Antarctic sea ice has been stable,” he says.

In the case of the Mackenzie, Nghiem notes, what makes the river water even better at melting ice in the Beaufort Sea is an annual barrier of “landfast” sea ice anchored to the shoreline. This barrier holds back much of the river’s discharge like a dam, allowing it to pond and continue warming until the barrier finally gives way, typically in early summer.

“Once it breaks through this barrier of sea ice, then boom, you send out the whole lot of warm water that can melt sea ice very effectively,” Nghiem says, more effectively than if the river slowly trickled into the Arctic. Moreover, winds driving the Beaufort Gyre ocean current were especially strong in spring 2012, helping fragment Beaufort sea ice earlier than usual and making it more vulnerable to melting.

The combined effect of strong Beaufort Gyre winds and a pulse of Mackenzie River water has acted to drastically reduce sea-ice cover in previous years as well, such as in 1998 and 2008, the team noted. Detailed monitoring of these features could thus help “forecast how big the open-water area in the Beaufort Sea would be [in a given summer], and that … would be advantageous for people who plan maritime operations in this area,” Nghiem says. However, he adds, more detailed readings of temperatures throughout the river water column — which would indicate its actual heating potential better than surface temperatures alone do — and details about how the river water mixes into the seawater are needed to complement satellite observations.

The Link LonkApril 18, 2021 at 06:10AM

https://ift.tt/3tGhzaQ

Warm river water melted Arctic sea ice - EARTH Magazine

https://ift.tt/2CoSmg4

Sea

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/CZF6NULMVVMEXHOP7JK5BSPQUM.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment