Raised in Northern California in the 1980s, seaweed has been a part of my diet since childhood. At a time when my rural Mendocino County hometown didn’t yet have a sushi restaurant, my mom would stock up on crispy, nearly translucent sheets of paper-like nori for us to roll our own maki sushi at home. And my favorite part of the miso soup we’d get on our trips to San Francisco’s Japantown was the chewy, slippery pieces of wakame that I’d slurp down with rich, salty umami broth and tiny cubes of tofu.

As a white kid growing up in a largely white community three hours from the nearest airport, mine was not a sophisticated understanding of seaweed as a culinary ingredient. But I also have no memory of thinking of it as significantly different from, say, spinach or broccoli. At the time, it never occurred to me that these ingredients, so familiar to me, were wild foods that, very possibly, could be found in the same tidepools my brother and I scoured for mussels to pry off the rocks and eat or abalone shells to add to our seashell collection. While I had long since understood that to be true, I knew very little about the wide world of culinary seaweed. So when I saw a sea foraging trip listed on Airbnb’s “Experiences” platform, I signed up.

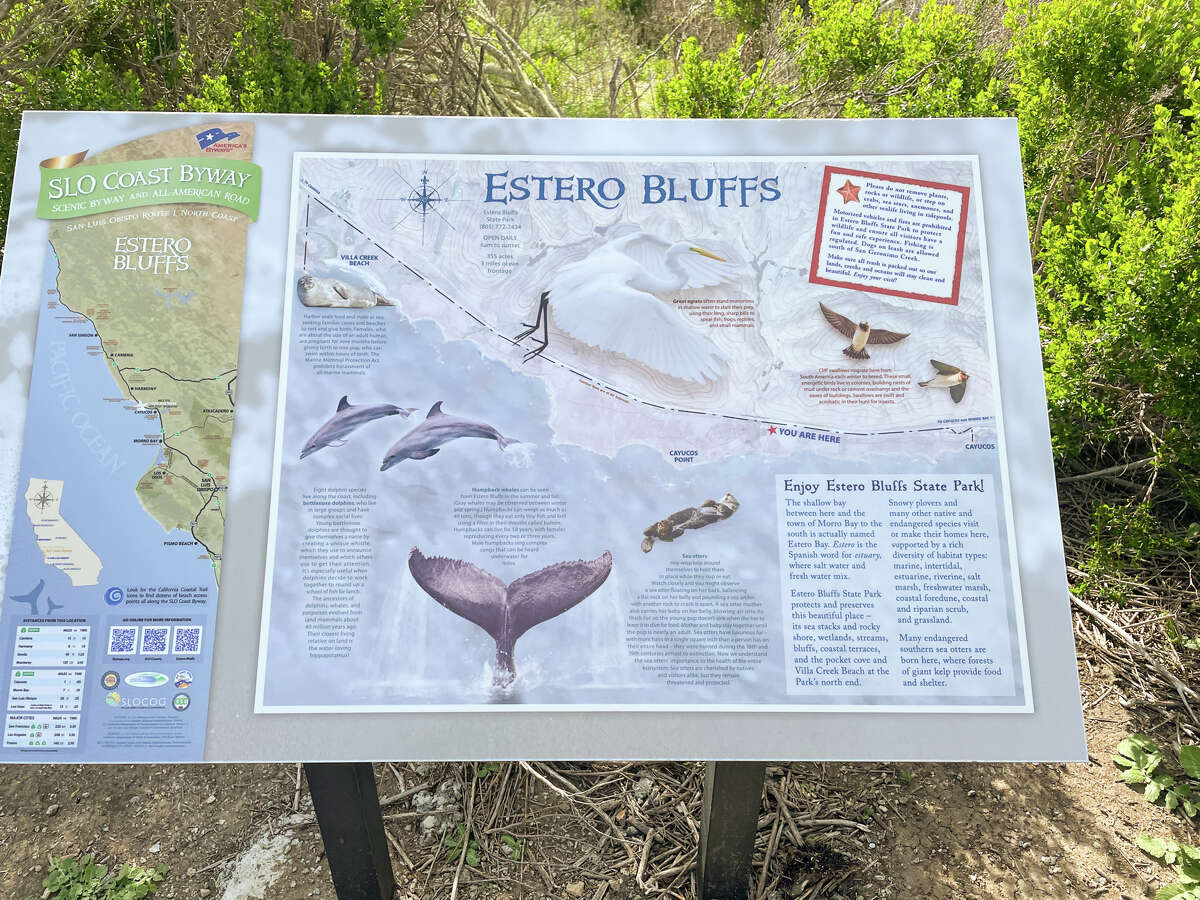

Just north of Cayucos, on California's Central Coast, the beach at Estero Bluffs State Park is a fine place to forage.

Freda MoonPart class, part “farm dinner,” the trip was hosted by Spencer Marley, a former journalist turned merchant marine turned seaweed entrepreneur, who has the kind of easy warmth that makes it hard to imagine him without a smile or some enthusiastic seaweed-related trivia springing from his lips.

I arrived at our 2 p.m. class a bit harried after being led astray by a particularly odd Google Maps glitch, but Marley immediately set me at ease, cracking a self-deprecating joke and assuring me my timing was just fine.

He was in no rush, he said. The seaweed wasn’t going anywhere.

The address of our meetup at Estero Bluffs State Park, north of Cayucos, had somehow been swapped with another, more famous park just up the coast: San Simeon, where Hearst Castle sits high on the hill and elephant seals make a scene down by the shoreline. By the time I realized the inexplicable mislabeling, I’d overshot the roadside parking lot where Spencer had, accurately, directed us to look for his gold Dodge pickup and had to backtrack by 20 minutes. While I’m generally loathe to be late, I was particularly frantic because I’d paid $125 to spend two hours on a beach with a stranger. This was a date I didn’t want to miss.

Spencer Marley, seaweed forager, with the tools of the trade.

Freda MoonWhen I pulled up, jumping out of my car and awkwardly speed-walking to meet my group, I found Spencer huddled with just two other would-be foragers, Emma and Henry, a couple from the Bay Area. They were making small talk about shoes — nobody seemed quite certain what to wear — and casually discussing their respective interests in harvesting wild seaweed. Spencer’s, like mine, went back to a childhood in Northern California (he’s from the South Bay). Henry and Emma, meanwhile, were transitioning to vegetarianism and trying to incorporate more environmental sustainability into their meals. (Though Henry, who worked for Apple, confessed, with dry humor, to being more or less content to live on packaged ramen when Emma isn’t cooking.)

Marley grabbed some plastic buckets from the back of his truck, along with a large blue backpack he hoisted onto his shoulders while cracking a joke about how he had almost certainly forgotten something. “I’m the most forgetful person on the planet,” he said, before handing out the mesh seaweed collection baskets and red-handled pruning shears — Swiss-made, rust-proof, and popular, Marley said, among the vineyard workers just over the hill in inland San Luis Obispo County’s wine country. He’d tried other tools but nothing has compared.

As we set off behind him, down the dusty dirt path through coastal shrubs to the nearby bluffs, he told us about the history of the property that was now a state park. It was once owned by a prominent local ranching and wine-making family who, a century before, had leased the tidepools to Cantonese seaweed harvesters.

Old sneakers are a surprisingly decent choice for navigating slippery, rocky tidepools.

Freda MoonWhen we got to the beach, I stashed my things on a large rock far enough from the water’s edge to hopefully keep them dry, rolled up the legs of my pants, and changed into the water shoes I’d bought that morning before wading from the gray sand into the tidepools with the others.

Marley started out with Phycology 101, explaining the intriguing biology of kelp, which is not a plant and not quite a fungus. Instead, it’s an oversized algae that reproduces by dropping spores, like mushrooms, and grows on every continent. For novice sea foragers, Marley’s point was to reassure: “Unlike mushrooms, where one bad call could zap your liver,” he said, “there are no toxic seaweeds in the world.” The biggest danger from harvesting seaweed isn’t the kelp itself, but the water — the run-off and the potential pollutants — it’s in. Freshwater algae, Marley explains, are another story: “Almost all,” he said, “are deadly toxic.”

Until recently, Marley had been operating a family-run seaweed business, harvesting prized kelp like kombu from the local shoreline with his three kids (twin 13-year-old boys and a daughter, 10) and selling it at weekend farmer’s markets for $10 per ounce. Marley now has a day job at Cal Poly and offers his foraging tours on the weekends.

A pile of freshly harvested wild wakame.

Freda MoonThis particular Saturday started out gray and chilly, as it often does along the Central Coast, where the marine layer can mean a 30-degree difference between the ocean and the inland area along Highway 101. But by the time of our excursion, the sun was out, which not only made for a more comfortable afternoon of trudging through the chilly Pacific, but had the practical advantage of helping to see the various seaweeds Marley was instructing us to spot.

He picks up a large piece of pyropia, a particular species of red algae that, Marley explains, is what nori is made from. It’s a slow-growing seaweed that’s found in the upper tidal areas of the rocky shoreline. Most of what we eat, however, is farmed and heavily processed. After it’s harvested, it’s pulverized in a large vat, pressed, and rolled into the paper-like sheets that are then dried or baked. Because it grows so slowly, and is constantly being bombarded by the decidedly non-peaceful waves of the Pacific, most of the pyropia we found was short, shaggy leaf-like pieces of translucent brownish-green algae that coated the rocks like a head of hair.

Marley showed us another seaweed, ulva, which he said was his second favorite to eat after kombu. Historically, it was a delicacy in what was then Canton (now Guangzhou), he says, in part because of its color, which resembles jade. He points to the hold fast, which is what connects the algae to the rock and the lamina, the leafy part of the organism, and talks about how even when the tide is high or the surf is big, it’s possible to forage along the beach without any equipment at all.

Spotting the difference between true and false kombu — one a prized ingredient, the other virtually flavorless — is surprisingly straightforward.

Freda MoonThe ocean, he says, is constantly gleaning — ripping pieces of kelp from the rock — and tossing it ashore. It is, he said, as if “a tornado went through a cornfield and you went and picked up the corn after.” Kombu, the Japanese word for kelp (though it also refers to a particular variety of seaweed with the unwieldy name laminariaceae), which grows in deeper water, is most easily harvested this way. It’s also, he says, often mistaken for a lookalike species, ilaria. It won’t hurt you to eat it, said Marley, but “it tastes like nothing.” But once you learn to spot the difference between the square edge of true kombu and the sharp, wavy blade of ilaria, you can easily find $100 worth of kombu in just an hour of foraging along the shore, said Marley.

As we hunted and learned, Marley had us taste the various seaweeds raw. The fan-shaped rock weed, or fucus, has a distinctive “olivey, briny” flavor, he noted, that is particularly satisfying raw but doesn’t hold up well to cooking. Other marine algae, he explained, is traditionally used in bathing and health treatments — as loofahs for scrubbing, and seaweed wraps for hydrating the skin, for example — in places like Greece and Ireland.

Everything seaweed forager Spencer Marley needs to feed a group can fit in a backpack.

Freda MoonMarley’s main reason for loving seaweed, though, is that it’s a sustainable source of nutrition and, “from a foodie perspective, there’s so much we haven’t done with it.” He eats miso soup many mornings for breakfast, but he also has seen his seaweed used in high-end restaurants in much less traditional preparations, tossed with vegetables in a salad, for example, or in an oyster Rockefeller-like dish in place of spinach, or cut into noodle-like strands and stir fried.

By this point, each of our baskets were increasingly full and it was time to rinse the seaweed, which was sandy from churning in the beachfront tidepools, and for Marley to make us lunch. He searched out a relatively level rock on which to set up his camp stove, pulled a large metal pot, a knife, an onion, and a couple of large cooking chopsticks from his bag along with a package of dried ramen noodles and a mild-flavored soy sauce. Those last two ingredients, he said, are the result of years of experimentation. He’s tried many dried noodles and varieties of soy sauce and these, he said, best highlight the sometimes subtle flavors of the fresh seaweeds.

Spencer Marley's harvester's noodle soup is a loving tribute to marine algae.

Freda MoonIt’s a simple soup, but that’s the point. He wants us to taste the flavor of the seaweed itself, which can easily be overpowered by too many other ingredients. And the soup, which Marley is happy to admit is exceedingly easy to prepare — a quick harvest meal, he calls it — was refreshing but satisfying, with layers of flavor that taste of the sea but are also surprisingly earthy. It had a depth of flavor, often called umami, that I don’t know if I’ve ever experienced in such a pure form. Sitting on the beach, sipping the broth from the small soup bowls Marley handed out, I thought about those little rectangular boxes of crispy, salty nori that are now ubiquitous playground snacks and how much bigger and richer the world of seaweed is than I had known.

More "Meals Worth the Trip"

May 17, 2021 at 10:52AM

https://ift.tt/3hwY15y

Sea foraging for kombu on California's Central Coast - SF Gate

https://ift.tt/2CoSmg4

Sea

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/CZF6NULMVVMEXHOP7JK5BSPQUM.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment